Recession over?

- 69.6%: The total capacity utilisation rate of US industry in August, which is 11 percentage points below the average rate of the past three-and-a-half decades

- 9.7%: The US unemployment rate, the highest in 26 years. Unemployment has risen from 4 per cent in March 2007 and continues unabated

***

It’s a bit like letting an audience decide how a movie ends. Think of the movie as being one of those comic book superhero ones, depicting the classic fight between good and evil. The good guys are the central bankers and governments who are valiantly fighting the dark and evil forces of recession as best they can.

So far it seems like the good guys, with a little help from the superhero, have a slight edge.

What’s next? Some people are big fans of ‘happy ever after’ endings and may be ready to believe the good guys are ready to dispatch the evil forces to their doom

|

That, in short, sums up the vastly differing beliefs of investors and economists over the past few months to the increasing but still tentative signs of a global economic recovery. Even as US Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke last month called the end of the deepest and longest recession in 80 years, equity and commodity markets have enjoyed a strong bull run in anticipation of good times

|

***

Crash and boom

Most markets and commodities have gained significantly from their lows

| Last traded value | Return since Lehman (%) | Increase over low (%) | |

| Equity indices | |||

| Dow Jones | 9,742 | -11.9 | 50.6 |

| S&P 500 | 1,061 | -12.6 | 59.1 |

| DAX | 5,714 | -4.2 | 59.2 |

| CAC | 3,814 | -6.7 | 54.7 |

| FTSE 100 | 5,160 | 2.7 | 49.1 |

| MSCI Latam | 3,660 | 11.9 | 120.6 |

| MSCI Asia ex-Jap | 454 | 20.8 | 96.4 |

| Sensex | 16,853 | 24.7 | 118.9 |

| Shanghai Comp | 2,755 | 38.7 | 65.4 |

| Brazil Bovespa | 61,235 | 24.4 | 108 |

| Russian RTS | 1,261 | 11.4 | 155.9 |

| Commodities | |||

| Crude oil ($/bbl) | 67 | -26.8 | 97 |

| Aluminium ($)* | 1,818 | -26.8 | 45.2 |

| Copper ($)* | 5,962 | -14 | 112.2 |

| Gold ($/oz) | 992 | 27.3 | 39.3 |

| Zinc ($)* | 1,856 | 7.4 | 77.3 |

| HRC ($)* | 598 | -40.5 | 33.5 |

From Aug 16, ’08 to Sept 29,’09; * per tonne

***

At times, it feels like Lehman never happened

|

It’s all being driven by investors who cling to the belief that despite being battered and bruised, their superhero — American consumers — will somehow manage to get back on his feet again and lift the global economy. Economists, however, don’t think that’s possible anymore, given the scale of the wealth destruction in the past year, and they are warning about a slow, grinding and painful march to recovery. They believe that the markets may have just about over-reached themselves in their attempt to cheer on their leader.

To economists, this is the harsh reality: protracted, patchy, anaemic and fitful. These are the words most frequently being used to describe the recovery underway in the US. “If I had to use a letter to describe the shape of the US recovery, I would say a W-shaped recovery remains the most likely scenario,” says Dr Scott Anderson, vice-president and senior economist at Wells Fargo. In other words, expect a bump up in economic growth in the medium term followed by a drop later, although not necessarily back to recession levels.

And why is that? In one sentence: American consumers can no longer afford to play superhero of the economy (local and global) anymore. Yes, superheroes have their downtimes too. Right now, they’re busy paying the price for indulging in some naughty behaviour in the past — spending way beyond their means.

Consumption, which accounts for about 70 per cent of US gross domestic product (GDP), is crucial to the health of the American economy. The extraordinary power of consumers to lap up everything from flat-screen TVs made in South Korea to the auto fuel made from oil pumped in Brazil, used to come from three sources: rising home and equity prices, super-easy credit and steady incomes from jobs. All three have been gnarled in problems since the past two years (stock prices have risen in recent months, but the gains are nowhere close to offsetting the vertiginous drops in others), that has forced consumers to hunker down for some tough times ahead.

Anatomy of a hero’s downfall

Let’s start with the housing market, the tinderbox that eventually caused the American economy to blow up last year. After the sub-prime crisis exploded in mid-2007, house prices tumbled, following wave after wave of house repossessions. Inventories of unsold houses climbed sharply.

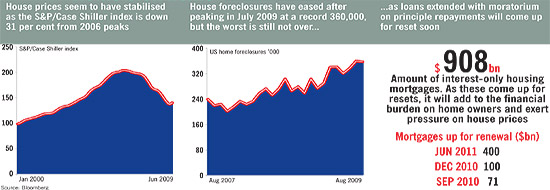

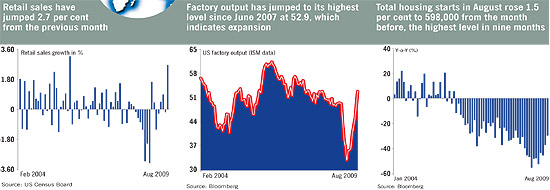

There are signs that the market may finally be on the mend. Total housing starts in August rose 1.5 per cent to 598,000 from the month before, the highest level in nine months. “First-time home buyers are taking advantage of the first-time home buyer tax credit, and investors are snapping up foreclosed properties on both coasts, pushing home sales higher and easing the inventory backlog,” says Anderson. (In a bid to rekindle growth in the housing market, the government announced a scheme — set to expire in November — under which first-time buyers of homes are entitled to an $8,000 tax credit.) The incentive and lower house prices (down by 31 per cent from their 2006 peaks, according to the S&P/Case-Schiller house price index) driven by record foreclosures (July saw a 2009 high of a little more than 360,000), have helped to stabilise the housing market in recent months, say experts (See chart: Home sick home).

But don’t let the slight improvement fool you. One in 10 mortgage borrowers in the US is behind on payments and one in every 25 homes is in foreclosure, Michael Williams, chief executive officer of Fannie Mae, the government-controlled mortgage company, said in a speech in Washington last month. Homeowners have lost 40 per cent of their equity, making refinance more difficult, he added.

And there may be more brick walls ahead. Thousands of mortgage buyers opted for ‘interest-only’ loans, which required them to make only interest payments first, putting off principal payments for several years. The interest-only period on many such loans will start to expire soon. Monthly payments for home owners could rise by 20-75 per cent once the principal is tacked on to interest payments. According to a study commissioned by The New York Times, there are 2.8 million active interest-only home loans totalling $908 billion. In the next 12 months, the study says, $71 billion of interest-only loans will be reset. After that, another $100 billion will be reset. By mid-2011, about $400 billion will be reset.

***

On Sale: Home sick home

***

The big problem is that many of these homes are still ‘underwater’ — worth less than the loans against them. “Housing is still threatened by another drop in demand this winter when the first-time homebuyer tax credit expires, foreclosures continue to rise, and home prices drop further,” warns Anderson. “I do expect another surge in interest-only mortgage resets, which could prove difficult to refinance especially if the mortgages are underwater. This could certainly dampen the recovery in housing, the banking system, and even impact overall economic growth.”

In baseball — the favourite sport of Americans — that’s strike one.Now let’s talk about easy credit. US banks continue to be weighed down by their sins of the past, when they handed out ‘no questions asked’ credit to even dodgy mortgage buyers at low rates, on the back of rising home equity (the difference between the market value of a house and what is still owed as mortgage). As prices were rising to stratospheric levels in housing markets, they also happily invested in all kinds of mortgage-backed securities. To finance their purchases, they shouldered large levels of debt (money was cheap then). When the sub-prime crisis hit, it was just a matter of time before their mortgage-related securities turned radioactive. “The largest write-downs since the onset of the crisis occurred on US mortgage-related securities as well as on leveraged loans, failed hedges and, increasingly, conventional loans,” says Jan Schildbach, banking analyst with Deutsche Bank Research in Frankfurt, Germany.

Banks on both sides of the Atlantic have written down more than $1 trillion from their assets, and the International Monetary Fund reckons they may have to take a further hit of $1.3 trillion. US regulators estimate that losses from syndicated loans by banks and other financial institutions tripled to $53 billion in 2009.

To prevent many large banks from going under, governments in Europe and the US were forced to extend credit lines totalling billions of dollars. One year after the collapse of Lehman, the world is still a tough place for banks. “As financial markets have stabilised, an expectation is taking hold that the worst may be behind us as regards mark-downs on securities (changes to accounting rules have helped too),” says Schildbach. “In the short-run, however, loan loss provisions will represent a further drag on profitability, pushing a sizeable share of banks into the red this year and the next.”

In the US, 95 banks have failed this year, up from the 25 last year. Expect more of the same going forward.

That has made banks wary of lending further, despite having millions of dollars at their disposal, courtesy the Federal Reserve’s emergency measures such as guaranteeing money market funds and accepting corporate bonds as collateral for lending to institutions. “Banks are more cautious about lending, and demanding more documentation,” points out David Wyss, chief economist for ratings agency Standard and Poor’s in the US. “That is probably good in the long run, although it is a drag on the economy right now.” All that money is being used to squeeze out excess leverage from banks’ balance sheets.

Not that borrowers are banging down their bank’s door for money either. The flush years had encouraged households to eagerly take on extraordinary amounts of debt, convincing themselves that their growing net worth (driven by sizzling house prices) would allow them to service the loans comfortably. By 2008, average debt to personal disposable income shot up to a record 130 per cent. The housing market collapse has left them struggling to pay down those steep levels of debt. “Overall, loan growth in the next few years should remain sluggish as households in several bubble countries (the US, the UK, Spain and Ireland) reduce spending and save more,” acknowledges Schildbach. “Credit losses, partly triggered by a surge in unemployment, may continue to weigh heavily on most institutions.” That’s strike two.

More jobless

Now let’s look at the steady income from jobs bit. More than seven million Americans have lost their jobs since the start of the recession in December 2007; the expectation is that thousands more will be out of work before things start to get any better. “A slow recovery means the unemployment rate will continue to rise even beyond the end of the recession,” says S&P’s Wyss. “We expect a peak in mid-2010, near 10.4 per cent.” Unemployment currently stands at 9.7 per cent, the highest in 26 years.

***

Hurt and broken

***

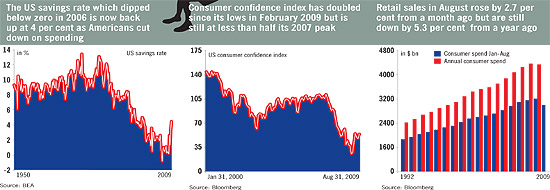

Is it any wonder then that Americans are no longer shopping as they used to and instead, are keeping aside a greater portion of whatever income they have left in their piggy banks? The savings rate, which dipped below zero in 2006, is now back up at 4 per cent. The average of the past 25 years has been about 5 per cent (See chart: Hurt and broken). “I’d say the savings rate could rise up to 8 per cent before falling back a bit again,” says Rob Carnell, the London-based chief international economist at ING Wholesale Banking. Frankly, it’s hard to see how Americans can save much more given their huge pile of debt.

It also makes spending yesterday’s story. The new story is all about the American saver. “American households have lost an incredible amount of wealth over the past two years, and home values continue to fall in many regions of the country,” points out Anderson of Wells Fargo. “This will keep consumer spending growth in check for some years to come.”

The Conference Board’s widely watched consumer confidence index — a gauge of how consumers feel about the economy and the jobs market — confirms that sentiment: while having improved moderately in recent months to 54.1 after plunging to a record low of 25.3 in February, the gauge is still a long way off its 2007 peak of 111.9.

The only glimmer of hope comes from the rally in stocks, which added $2 trillion or 3.9 per cent to the net worth of households, estimated at $53 trillion, in the second quarter of this year. An encouraging sign, but it doesn’t compensate for the whopping $13 trillion they lost in 2008.

That’s strike three, and throws consumers out of the game.In short, we have a stupor-inducing combination of recovering, yet fragile house prices, tighter or low access to credit and increasing job losses, all of which should tilt the balance in favour of savings rather than spending. “This sets a low speed limit for economic growth going forward, and one cannot rule out the possibility that once fiscal stimulus fades, growth will shift lower or contract once again,” says Wells Fargo’s Anderson. “Not a great environment for a robust rebound.”

You can say that again. It echoes the sentiment of Paul Krugman, Nobel prize-winning economist, who wrote in The New York Times that “the economy will be stuck in purgatory for a prolonged period.”

In search of new heroes

So if American consumers can’t play superhero, who can? Enter the new rescue duo of Batman and Robin, a.k.a Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke and the Obama administration.

After missing some key signs of the snowballing credit crisis in 2007, Bernanke redeemed himself quite honourably last year after fighting valiantly to prevent the financial and housing markets from collapse by announcing a series of rapid-fire measures. More than $1 trillion was injected into the economy via 10 main support programmes (most of which were highly unconventional). Chief among them was buying $300 billion worth of longer-term treasuries (ending this year) and up to $1.25 trillion in mortgage-backed securities and agency debt issued by government-owned mortgage guarantors such as Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. These agencies buy mortgages from lenders, securitise them and sell them as mortgage-backed securities to investors. When such securities are sold at high prices (offer low interest rates), they can guarantee the underlying mortgages at low rates as well, which in turn, allows the lender to offer low rates to home loan seekers. The Fed is estimated to be buying up to 80 per cent of mortgage-backed securities in the market.

It has certainly helped to revive confidence in the money markets. The Libor (London Interbank Offered Rate), a benchmark rate for interbank lending, has now dropped to 29 basis points from 4.82 per cent last September. Similarly, the Ted spread (the spread between government treasury bills and interbank loans of similar tenure) has also narrowed to a saner 21 basis points from 4.49 per cent a year ago.

The problem is the real economy. It seems that banks and other financial institutions are still not lending with gusto to businesses and consumers. What are they doing with the money? They received the cash gratefully enough, said ‘thank you very much’ to the Fed and then promptly turned around and parked it in interest-free reserve deposits with the central bank. From $47 billion in the week ending September 17, 2008, reserve deposits with the Fed have ballooned to a staggering $868 billion now. It seems that after watching so many banks turn into fallen angels last year, they’re still having nightmares about being the next one to come apart at the hinges. Like consumers, the lenders too seem to be saving for a rainy day.Still, you have to credit Bernanke for trying really, really hard.

Joining in

The Fed chief’s extraordinary rescue measures were backed up in early 2009 by the Obama administration’s $787 billion fiscal stimulus package. Is that working any sort of magic on the economy? Truth be told, it’s going to take time before it feels the full adrenaline jolt, because less than 20 per cent of the money has been spent so far. According to White House data, about $151 billion had been pumped into the economy by the end of August, of which $62 billion was in the form of individual and business tax breaks.

***

Green shoots

***

Overall, the stimulus package — designed to stretch up to 2011 — will allocate about $499 billion on spending on infrastructure and other projects designed to create jobs; the remaining $288 billion consists of tax cuts. Most of the spending was projected to happen in late 2009 through 2010. “A significant portion of the current stimulus has still to come through,” says Kevin Grice, senior international economist at Capital Economics, a London-based economics research outfit.

Nevertheless, even the few incentive schemes the package has rolled out have managed to shake their targeted industries into hyperactivity, at least for a while. The cash-for-clunkers scheme is a spectacular example of that. The scheme offered up to $4,500 for automobile owners to trade in their old models for more fuel-efficient ones. The incentive programme (which expired in August) was initially allotted $1 billion, but was handed an additional $2 billion as it became a runaway success with motorists. It provided a much-needed boost to the beleaguered car industry, whose sales were lifted by 700,000 units.

The effect was seen in August retail sales (including auto sales) figures, which jumped 2.7 per cent from the previous month. “The fiscal stimulus programme is already showing up in the data, particularly the cash-for-clunkers scheme which has lifted retail sales and will be the key factor behind Q3’s likely return to positive GDP growth,” points out Grice. Some experts believe that similar schemes across different industries are being planned by the government in an attempt to keep consumer spending going in the medium term, at least moderately. Stimulus spending has also helped to improve factory output as indicated by the index from the Institute for Supply Management, jumping to 52.9 in August (the highest since June 2007) from 48.9 in July. A reading above 50 indicates expansion.

But stimulus packages can only provide short-term fizz; what happens after all such schemes have been exhausted? The idea of a stimulus package is to have the government spend on investment and job creation until the private sector becomes strong enough to do so. Right now, there is absolutely no indication that the economic recovery is self-supporting (driven by a strengthening private sector). Without the crutch of the stimulus package, it’s possible the economy may not have even hobbled forward. Programmes like the cash-for-clunkers may give a light bump up to growth for a couple of quarters, but with businesses and consumers yet to get back their groove, growth will remain choppy, rising a couple of quarters and then falling back the next.

Deja vu?

While it is undeniable that both Bernanke and the Obama government have lent a steadying hand to the economy, no one expects them to supplant the American consumer as the new heroes propping up the economy. It’s true that they steered the economy out of a near-death experience, but their heroic efforts mask the same bad behaviour (admittedly, more for the government than the central bank) that put American consumers out of action, that is, spending way beyond their means. The Fed, for instance, has expanded its balance sheet to $2 trillion, up 130 per cent from $869 billion in August 2007. Meanwhile, the government is all set to run a $1.6 trillion deficit in 2009 for its attempts to pull the economy out of its deepest recession in decades. How will it make up this budget gap? Inevitably, by raising taxes or cutting spending. Some experts betting on the second option happening as early as the second half of next year.

Clamping down on spending just as the economy is staging a fragile recovery could keep growth below trend for some time, say experts; on the plus side, there’s little to worry about on inflation. “The recessions have been deep and opened up a great deal of spare capacity,” points out Grice. According to Federal Reserve data, US industry was running at 69.6 per cent of total capacity in August, 11 percentage points below the average rate of the past three-and-a-half decades.

Inflation — rising prices — occurs when demand outstrips supply. The available spare capacity, say experts, will allow supply to easily and quickly catch up with a rise in demand, whenever that happens, making the idea of ‘soaring inflation’ a far-out idea at the moment. “Deflation, we believe, is the bigger near-term risk, not inflation,” says Grice.

What about all those billions of dollars sloshing through the US financial system? With the appetite to lend low, the money is not exactly ‘going forth and multiplying’ in the form of bank credit. Yes, the monetary base (currency in circulation plus bank reserves) has exploded, but that’s mainly because of the stratospheric rise in reserve deposits with the Federal Reserve.

The monetary base is what allows banks to lend money and create the ‘money multiplier effect’ (an expansion in money supply because of an expansion in bank credit). Right now, there’s no such effect. “Till that money doesn’t go out and chase goods and services or generate further credit, it has no relevance for inflation or the currency,” points out ING’s Carnell.

Soon, it will be time to leave

High spare capacity, widespread unemployment and low credit creation are the reasons for the near-universal view among top economists that interest rates will stay low in the US, the UK, Japan and the eurozone for most of next year. That doesn’t mean that a recovering economy won’t prompt the central banks to normalise policy on other fronts. “Overall, it is more likely that central banks’ first step will be to remove parts of their unconventional monetary stimulus measures before hiking interest rates,” explains Sebastian Becker, an analyst with Deutsche Bank Research in Germany. “As regards the central banks’ temporary monetary stimulus measures, one way to withdraw money would be to simply not roll them over once they mature. Concerning the central banks’ asset purchase programmes, central banks could start selling parts of these assets again if they conclude that markets are again willing and able to have the capacity to re-absorb these assets.”

The Fed, for one, is already thinking about that option. Media reports suggest that the Fed is mulling borrowing money from money market mutual funds as part of eventual steps to withdraw surplus money from the system. Experts figure the move could suck out $400-$500 billion from the markets, with the Fed using reverse repurchase agreements to sell mortgage-backed securities and treasuries it bought during the crisis.

“Monetary authorities also have the option of withdrawing money from the system by, for example, simultaneously increasing the key interest rate as well as the interest rate paid on the banking sector’s excess reserves at the central bank,” says Becker. “By hiking the deposit rate above inter-bank money market rates, monetary authorities would clearly give commercial banks the incentive to deposit their excess reserves at the central banks instead of using them for credit expansion.” That may also be in the works, according to American media. “Finally, central banks could issue debt instruments with attractive (above-market) interest rates to absorb liquidity,” he adds.

Across the Altantic, European governments aren’t having much luck either as they poke and prod their disparate economies back to life. The eurozone is showing signs of limping out of the recession gate (France and Germany, its two biggest economies, have already crawled out with 0.3 per cent growth each in the June-ended quarter), but don’t expect them to pick up the pace any time soon. “The UK is on the verge of emerging from recession too, but its upswing will be weaker than is likely to be the case in the big Euro-zone economies, particularly Germany and France,” predicts Grice of Capital Economics. The countries may be different but the problems are the same old: a fragile housing market; wary banks still nursing steep losses on mortgage-backed securities and other indiscriminate lending; and debt-burdened consumers (more in the UK than in Europe).

There are no superheroes to be found here either.

Time to shine, Asia

So if US consumers can’t spend like before and Europeans can’t pick up the slack, who possibly can?

Say hello to Asia, to whom the baton of global growth has already been passed. After initially being knocked down by the global credit crisis, Asian economies have rebounded quite strongly in the past few months. “Asia is leading the global recovery and will continue to do so,” says Rajeev Malik, regional economist at Macquarie Securities in Singapore.

Credit the ultra-loose monetary policies and fiscal stimulus packages announced by governments across the region for this economic resilience. “These policies helped to cushion the blow of the global recession to some extent,” says William James, principal economist at the Asian Development Bank in the Philippines. “East and South Asia, in particular China and India, are growing more rapidly than expected.” Noting this development, the Manila-headquartered bank recently upped its 2009 economic forecast for developing Asia to 3.9 per cent from the earlier 3.4 per cent.

China maintains its regional star performer rating as its mega $585 billion stimulus package, partly being implemented through extremely generous bank lending, looks set to ensure that the economy expands by the targeted 8 per cent this year. “China, India, Indonesia, South Korea (by contracting less than expected) and Vietnam are the key economies changing the picture of Asia for the better,” says James.

It helped that unlike the US or Europe, which were assaulted by a swift banking crisis in the wake of the credit crunch, Asia faced no such problem. The region’s banks had little or no exposure to the toxic mortgage-backed securities that wrecked many American and European banks. Conservative Asian consumers have also yet to develop an infatuation for debt-driven spending. In that sense, both banks and consumers remained relatively insulated from the woes of the developed world.

However, the region’s exports — a growth driver for nations such as China, Japan and Singapore — fell sharply in the aftermath of the global financial crisis. In recent decades, most of the region’s economies became addicted to exports, believing it was the quickest way to growth. Chinese exports, for instance, account for 33 per cent of that country’s economic activity. “Both the US and Europe are important end-destinations for Asian exports, which is why a sustainable recovery in these countries is important for any long-lasting recovery in Asian economies that are export-dependent,” says Macquarie’s Malik. But that may mean a long wait for Asia, given the unwillingness of American and European consumers to shop right now.

However, the region’s exports — a growth driver for nations such as China, Japan and Singapore — fell sharply in the aftermath of the global financial crisis. In recent decades, most of the region’s economies became addicted to exports, believing it was the quickest way to growth. Chinese exports, for instance, account for 33 per cent of that country’s economic activity. “Both the US and Europe are important end-destinations for Asian exports, which is why a sustainable recovery in these countries is important for any long-lasting recovery in Asian economies that are export-dependent,” says Macquarie’s Malik. But that may mean a long wait for Asia, given the unwillingness of American and European consumers to shop right now.

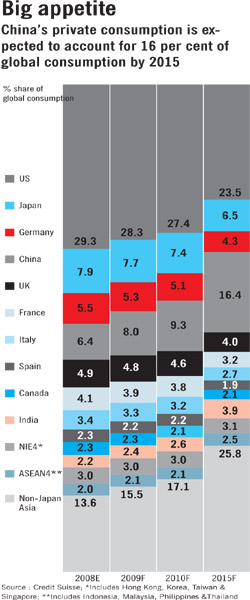

That’s why many commentators are calling on the region, in particular China, to lead a ‘global economic rebalancing’ and establish a new order in international trade. Their demand: they want trade-surplus (value of exports greater than imports) nations to shift away from depending on exports to debtor countries such as the US and focus on stirring up local consumer spending.

That may seem like making a virtue out of necessity, but undoubtedly, it works to the advantage of nations like India, which are likely to gain more ‘street cred’ with investors as its economy is already domestic demand-driven. India’s vital economic stats have also improved in recent months and is likely to garner more attention as the world adjusts to an economic order no longer dominated by American shoppers. Exporting fanatic China is also experimenting with the idea of stoking domestic demand in its stimulus programme (a portion focuses on raising rural spending on cars, houses, services and tourism), but its most visible way of doing it — via explosive bank lending — seems to be also blowing up dangerous price bubbles in stock and housing markets.

Singapore, South Korea and Hong Kong are also suffering a similar problem: growth is returning, but so are inflated prices in asset markets. That’s why most economists are betting that the region will be the first to exit the easy money policies they implemented last year. South Korea and India (already grappling with soaring food inflation) lead the list of possible countries to announce a withdrawal of excess liquidity early next year. For the moment, growth remains the priority. “Policy makers will want to be sure that the growth upturn is sustainable,” says Macquarie’s Malik.

Equity markets, meanwhile, have soared on prospects of a stronger recovery in Asia. The Sensex has soared by 72 per cent this year and experts believe it could keep climbing. (See accompanying report on the Outlook for Indian equities.)

A strong growth momentum has also led to rising murmurs about the possibility of China donning the saviour suit, but experts say it’s too early to make a hero out of the Asian nation. For one thing, by GDP, China is still too small to step into the US’s boots. In 2007, China’s economic activity accounted for less than 20 per cent of that of the US. For another, consumer spending accounts for a low 35 per cent of economic activity, the lowest among any major nation. Its total imports account for just a quarter of imports taken in by the US and Europe. Most imports are also commodities and raw materials and intermediate goods, which are then re-exported.

Clearly, there is a difference between leading the global recovery and lifting other nations out of it. “It’s like finding another gear when your car won’t start,” says ING’s Carnell. Despite the explosion in Chinese demand for everything from oil to autos in recent years, the health of the world economy still depends on how the US is doing. And clearly, the prognosis isn’t that good. For equity investors, it’s time to take a reality check. (See accompanying report on the Outlook for global equities and commodities.) Experts are calling it the new normal. Put another way, it’s going to be a long hard grind to the top.

Grice of Capital Economics sums it aptly: “We’re not going to see the global economy grow at 4-5 per cent, like it did during 2003-2007, for some time.” Welcome to the new normal.

No comments:

Post a Comment